– 31 May 2024 –

Janus:

For the past few decades, the system has made considerable fuss over what they sometimes call “the browning of America,” or “America’s multicultural future,” or “New America.” These slogans describe not only a future United States where a non-white majority replaces the old white America, but they also describe an increasingly pluralistic, “inclusive,” and “equitable” America where so-called alternative lifestyles and fluid identities replace the Christian social norms of the past. In other words, according to these people, the future of the overall United States will follow the present-day trends of America’s largest cities and their suburbs.

Brown America replaces white America. Multi-cultural America replaces Christian America. And New America replaces Old America.

If current trends continue, then these social programmers are certainly correct. New America is rapidly on track to replace Old America. And the system makes it sound like this transformation is an inevitable fact that just sprang out of the ether.

But this isn’t the first time a New America ended up dominating the Old.

Old America

A few weeks ago, this site shared some excerpts of 19th century books that warned against the growing urbanization in the United States at the time and what this could mean for the country’s future. Though one excerpt took a somewhat pessimistic view and the other an optimistic one, both authors warned that the growth of America’s largest industrial cities, with all of their crime and vice and lack of traditional American Christianity, could ultimately dominate the country and overwhelm it with foreign, urban, and generally un-Christian attitudes.

Now, almost 140 years after those books were written, any halfway observant “heritage American” can see very clearly that even the most pessimistic view from those days ended up falling far short of the post-Christian, post-American nightmare that besets us today.

But those good Christians of the 1880’s weren’t thinking that far ahead. They were talking about their relatively near future. The future that they feared was that which happened by the 1930’s and 1940’s: the domination of the new urban immigrant cities over the traditional Christian and Anglo-Saxon America that had previously, more or less, directed the course of American history up to those times.

In the 1880’s, the United States remained a majority rural country, with 22.6% of the citizens living in cities and towns in 1880, according to the US census, a figure that grew to 29.2% by 1890. In the 1880’s the United States was just starting to mend the regional divisions that had brought about the Civil War of twenty years before. The sectional attitudes and interests of the United States, from its founding up to that time, had reflected the cultural and economic split between north and south, and to a lesser extent, the east and west.

If the main socio-political forces of the United States until the 1880’s could be summarized in sectional terms, the Northern puritanical and mercantile classes struggled for power and influence with the Southern agrarian classes while the growing Western pioneer and yeoman classes tended to settle into one camp or the other while adding their own wild elements to both.

These sectional divides reflected the state of affairs in the United States throughout all of its history up till that time. It’s worthy to note that most college history courses on American history, at least until recently, tend to divide their courses at events before and after 1877. The main reason for this is that the socio-political forces that arose after the end of Southern reconstruction present a useful dividing line that year, and history post-1877 tends to represent the rapid transition of the United States from a rural and isolated country into an urban and imperialist one.

The Progressive Era

1890 is often considered to be the beginning of what we now call the “Progressive Era.” Between 1890 and 1920, social activists in the United States pushed for—and very often won—substantial political reforms to bring about increased democracy, government oversight, professionalism, and overall centralization and standardization of society along scientific and secular lines. Their efforts established electoral reforms, school standardization, improved sanitation and food safety, labor reforms, alcohol prohibition, and women’s suffrage, for example.

Overall, these Progressive reformers believed that, through the coordinated efforts of government, business, and civic organizations, they could scientifically and morally perfect human progress and the human condition. To the Progressives, the past was a problem to be solved; and a modern, collective, scientific future presented the solution to that problem.

Most historians seem to treat the activists of the Progressive Era as a single social force that manifested itself differently in urban areas versus rural areas. In some ways, this view is correct. The spirit of the times amounted to an overall reaction against the excesses of the post-Civil War industrialists, robber barons, and corrupt political bosses of all stripes. But if we start backward in time and look forward from the 1880’s, as the people of the times would have viewed the situation, rather than the other way around (as historians see things in hindsight), it seems more clear that two separate social forces drove two distinct sets of changes during these times, sometimes working together when their interests aligned, and more often working separately or in opposition to one another. These two forces were rural America and urban America, or, to put it differently, Old America and New America.

The Rural Progressive Era

During the Progressive Era, rural Americans were suffering under the excesses of the bankers and robber barons. Cash was hard to come by, and bankers could hurt the farmers more ruthlessly than nature itself. In some parts of the country, sharecropping was the norm; with farmers giving a portion of their crop to a usually absentee landowner. Railroads often charged outrageous rates for carrying livestock and harvests, especially when they operated as a monopoly in a given area and when markets were distant. On top of this, because of high national tariffs that protected city industries, farm exports were stifled. As more and more land came under cultivation, crop prices tended to drop, reducing any gains of the farmers.

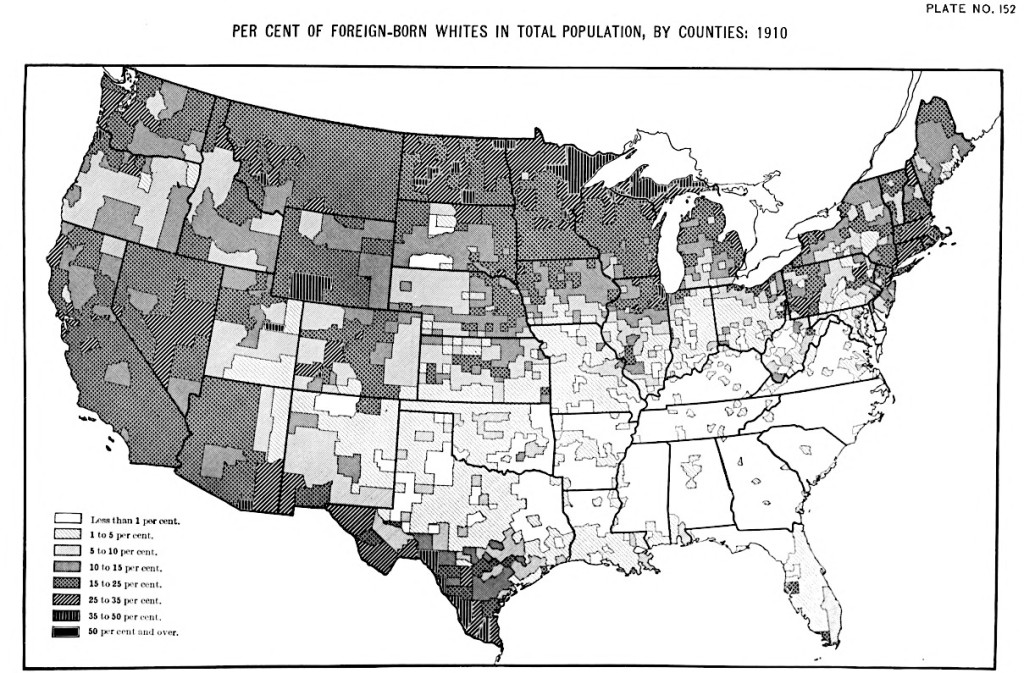

Demographically, Old America retained the United States’ original regional distinctions between north and south, and east and west. These areas included the descendants of the original American colonists but in areas outside of the the South reflected, to varying degrees, the waves of agricultural immigrants that had begun to grow substantially in the 1840’s with German and Irish settlers. In the 1870’s and onward, settlers from Germany and Scandinavia poured into the upper Midwest, sometimes becoming the majority in remote parts of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Dakotas. In the South, immigration wasn’t much of a factor, and there white farmers needed to align with white townspeople in order to maintain what came to be known as “white supremacy.” In the West, farmers lived more at the mercy of the railroads, and they often suffered under the power of ranchers in their states and territories, who often violently enforced a fence-less free range for their cattle. But despite these regional and ethnic differences, the rural population shared many of the same difficulties across the country.

In these rural areas, the spirit of the times gave rise to what became known as Populism. Organizations like the Grange and the People’s Party (Populist Party), boasting membership of hundreds of thousands of farmers, fought for improved prices and monetary policy and for laws to break the power of the railroads. Democratic alliances, especially in the West, pushed for the popular elections of Senators, for referendums, recall elections, and women’s suffrage. Politicians like William Jennings Bryan made names for themselves in their promotion of “free silver” to replace the gold standard.

Meanwhile a series of Christian revivals, later called the Third Great Awakening, swept the rural areas. This awakening can be divided into two main forms. First, the “Holiness movement” sprang from earlier Methodist teachings, emphasizing a second work of grace called entire sanctification. Then there was the Pentecostal movement, which taught the concept of a “baptism in the Holy Spirit” that manifested in acts of healing, prophecy, and speaking in tongues. These movements invigorated or challenged rural Christianity during these times, and they often drove the calls for rural social and political reforms, especially in calls to ban alcohol and promote rural schooling.

The Urban Progressive Era

In most history books about the Progressive Era, the writers will give most attention to the reforms demanded by the people of the cities and considerably less towards events in rural areas. This makes sense, as most educated people end up living in the cities and see events through the city point of view, and educated people are the ones who tend to write the histories and read them.

In general, the urban reformers of the Progressive Era, as mentioned earlier, sought to bring about social improvements through direct government action in conjunction with academia, business, and civic institutions (including urban churches.) And these reformers largely succeeded in their efforts, ultimately bringing about electoral reforms, government regulation of industry, improvements in public utilities and sanitation, trust busting of monopolies, standardized education, bank reform, the prohibition of alcohol, and women’s suffrage, among many other reforms.

Out of these reformist efforts, the urban forces forged a new socio-political structure in America, one that had never existed before. The new professional cultures of the increasingly secular, educated, Old American urban middle and upper classes aligned with the foreign, non-Protestant cultures of the new urban immigrants. To maintain their status in the midst of an increasingly foreign population, the traditional “WASP‘ urban elites of the northest formed sometimes uneasy alliances with the leaders of recent immigrant groups that had largely taken over the populations of America’s largest cities in the Northeast and Midwest. These immigrants were Catholics from Ireland, Italy, Poland, the Austrian Empire, and other parts of Eastern Europe as well as Jews mainly from the Russian Empire.

The history of the Progressive Era, in many respects, is the history of this alignment between the old American upper and middle classes with these alien newcomers.

The First New America

In the 1880’s, America’s largest cities were home to a rapidly growing number of immigrants, but the cities were still ruled and largely populated with the descendants of the original settlers. From the 1870’s to the 1910’s, the bulk of American immigrants, now romanticized by the processing station at Ellis Island and Emma Lazarus’ poem on the Statue of Liberty, moved to the larger cities and numerically dominated them, and their descendants tended to stay in these cities. They lived in ethnic neighborhoods while the original working class population gradually moved to the suburbs or settled in other states. The elites of these cities tended to stay put or move to the nearby suburbs, but they had too many connections to leave their strongholds or give up power easily.

The middle to upper class Old Americans who stayed near the cities originally tended to uphold very traditional and conservative social and religious values, yet the Progressive Era brought about new reforms that came to be known as “the Social Gospel.” The respectable, older Protestant denominations in the cities embraced the notion that the mission of Christianity was to better the lot of mankind on earth through social and political action. By improving people’s living standards, they assumed that the public morality would improve. Then naturally such enlightened people would embrace this civilized variant of Christianity. Often the highly educated leaders of the Social Gospel movement had a very liberal view of theology, and they increasingly emphasized worldly concerns over strict doctrine. Over time, these elite Protestants embraced a tolerant view of Catholics and even Jews, especially in the public arena. Meanwhile, as the immigrants swamped the populations of these cities, the Old American urban elites formed alliances with them to garner their support. Out of these alliances grew many of the Progressive reforms that materially helped the poor while enriching the elites.

To a lesser extent in most areas outside of the South, rural America also transformed into a New America because of immigration. In many ways, the large numbers of immigrants affected the culture of these areas to the extent of their numbers and their foreignness. On the whole, this wave of immigration tended to Germanize many areas of the North and West, transforming the old rural America into something a little different. These immigrants, for instance, disproportionately supported the centralizing reforms of the Progressives. But the nature of this rural immigration was different. These groups were not able to clump together in large ethnic neighborhoods close to their work as city immigrants could. By the nature of rural living, they were diffused across wide territories and had more interaction with the Old Americans. Because of these factors, and because they were ethnically closer to native-born Americans, they more quickly assimilated and merged into American life with fewer disruptions to older ways when compared to the later immigrants in the large cities, who were more often Italian and Eastern European.

The 1920’s

In the 1920 census, for the first time in US history, a majority of the population lived in American cities and large towns. By this time, foreign-born people comprised 13.2% of the population, and most of these foreigners and their descendants lived in the largest, most industrialized cities.

Among the people of Old America, particularly in the non-urbanized states, sentiment was growing against the increased influence and dominance of these large Northern cities with their foreign populations and non-Protestant religions along with the cities’ secular and overbearing elites.

Part of this resentment manifested itself in the heated religious debate between mainline Protestants of the large Northern cities and the traditional Christians centered in rural areas and the South. This disagreement led to a schism between modernists and fundamentalists that split largely along urban and rural lines. The attitude of this urban/rural divide was exemplified by the 1925 Scopes show trial, in which William Jennings Bryan contested the teaching of evolution rather than creationism.

Resentment of the growing power and influence of these industrial Northern cities also expressed itself in the Southern Agrarian literary movement. Southern Agrarian writers criticized the growing influence of progress, secularism, industrialism, and large cities. Their views amounted to an updated version of Jeffersonian democracy. They contributed to a very influential and contentious book, I’ll Take My Stand: The South and the Agrarian Tradition, published in 1930. Naturally Northern and urban critics dismissed the work as overly romantic and backward.

In addition to the religious and sectional divide, this rural resentment of the growing power of these large, foreign, increasingly non-Protestant and secular cities helped to generate support for consciously white, Protestant political movements. This anger inspired a new form of the KKK that was kicked off by the movie The Birth of a Nation, and it ultimately generated calls to curtail immigration from non-Protestant, non-white countries. From this racial and religious sentiment against the Northern cities sprang the 1924 Immigration Act that effectively ended mass immigration to the United States (until the 1965 Hart-Celler Act.)

The Cities Win

While the 1924 Immigration Act slowed down the growth of US cities, the disruption was already established. This represented the last real change in the overall system that rural America was ever able to achieve. A significant portion of the Northern elites based their power on the large industrial cities, and increasingly the new American culture that sprang from these cities spread outward across the country in the form of cinema and radio, largely dominated by increasingly wealthy Jews.

On top of this, especially since the 1880’s, more and more Americans from rural areas and small towns were leaving the limitations of their birthplaces for wealth and education in the urban centers. This fed a brain and population drain from the rural areas to the cities, depriving rural areas of some of their most intelligent and talented people.

Once people moved to the cities and suburbs from the countryside, they and their descendants rarely left these areas, except perhaps to migrate to other large cities across the country. Until very recently, once a family had left rural and small-town America, neither they nor their families would ever venture far from the comforts and culture of a metropolitan environment. And once they lived in a city, they tended to breed into the city population, with many “melting pot” ethnic backgrounds from unions between New England Protestants with Catholic Italians or Irishmen, between cultural Christians and secular Jews, etc. In some ways, the people of these large cities have become genetically distinct from Old, rural America.

To the multi-generational city people and suburbanites, the first New America is the only America that they really know or understand. They see all of the United States through the lens of their overwhelmingly dominant culture. To them, they are the real America! Some of them are surprised if they find out that the whole country isn’t like them. Others find rural/small-town America to be creepy, the basis of modern horror movies; or stupid, the butt of their jokes about hicks and hillbillies; or even idyllic, home to quaint but boring little families who still celebrate hearth and home. In fairness, ruralites can have some rather ignorant ideas about city people, too. The divide is real!

Conclusion

By the end of the Progressive Era, the founding-stock Americans who stayed near the large cities of the North had more or less settled into a union with recent immigrant groups who were largely Catholic and Jewish. Meanwhile, the countryside (apart from a few far northern sections of the country), though often altered with rural waves of immigrants, largely retained the culture, faith, and heritage of its settler populations. In effect, the first New America was a distinctly urban phenomenon. With the rise of mass media in the 1920’s and the numerical dominance of city-dwellers, gradually the media culture, the wealth, and national power in the United States reflected the collective mindframe of this urban New America, and this culture, wealth, and power increasingly directed national affairs.

Over the succeeding decades, people from these old industrial cities gradually colonized southern California, south Florida, Las Vegas and other places, and their culture continues to dominate in those cities to this day. Other cities have grown around the country, but until recent decades, they retained something of a continuity with the culture and heritage of their surrounding countryside in a way that the older hybridized cities of the North, the first New America, did not.

Effectively, thanks to the growth of the large cities and the decline in the farm population, the first New America managed to dominate the old United States by the 1960’s. They directed the wealth, education, culture, and political direction of the country from that time on.

And then the 1965 Hart-Celler Act opened the gates that brought in the vast numbers of non-white immigrants that, in the short run, allowed the elites from the first New America to further dominate and then repress the first Old America.

Increasingly, much like the original Northeastern WASP’s melded into the immigrant waves of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the hybridized and increasingly liberal “first New American” elites of the cities are uniting with this most recent, non-white, second “New America” that champions ethnic minorities, multiculturalism, and globalism.

Together with the new, non-white immigrants, this new elite plans to fully displace the original Old America as well as those whites from the first New America who have the audacity to resist the looming Brave New World and its non-white, non-Christian future, which they call “inevitable.”

When of one mind, Janus' views

form a composite of his two main sides. He attempts to consider issues with care and thoughtfulness, though he remains biased towards Christianity and Western

traditions. Outsiders might call him a Conservative, but in fact he is a Fundamentalist in that he promotes the Christian values that raised Western civilization to its peak.

When of one mind, Janus' views

form a composite of his two main sides. He attempts to consider issues with care and thoughtfulness, though he remains biased towards Christianity and Western

traditions. Outsiders might call him a Conservative, but in fact he is a Fundamentalist in that he promotes the Christian values that raised Western civilization to its peak. Tending to sensationalize, and sometimes to hyperbolize, C. F. van Niekerk over-analyzes any number of subjects from mundane minutiae to the great philosophical questions of life itself.

Tending to sensationalize, and sometimes to hyperbolize, C. F. van Niekerk over-analyzes any number of subjects from mundane minutiae to the great philosophical questions of life itself. Katáxiros, the parched one, alone and adrift at sea, yet ever rowing ahead anyhow, sometimes weakly and sometimes vigorously, thirsting after God through the Orthodox Christian Church, contemplating the ways of the Lord, recognizing that while he is inadequate to the task, he must press ever ahead. Katáxiros writes about matters pertaining specifically to the Orthodox Church.

Katáxiros, the parched one, alone and adrift at sea, yet ever rowing ahead anyhow, sometimes weakly and sometimes vigorously, thirsting after God through the Orthodox Christian Church, contemplating the ways of the Lord, recognizing that while he is inadequate to the task, he must press ever ahead. Katáxiros writes about matters pertaining specifically to the Orthodox Church. We don't know what to make of the Wanderer. He walks in with the moon and rolls out with the wind. He uses no name; the smells of rank sweat, dirt, and smoke mark him as much as anything. He's always near, but never close. Heedless of human ideals and bounds, he stands unyielding for honor on the ground. He's practical to a fault when he's not romantic to even greater fault. He says little, but when he does finally speak, we listen up. The Wanderer is our lawman of final resort. By hook or by crook, he sees a job done, just don't ask how. Frankly, we're a little afraid of the Wanderer.

We don't know what to make of the Wanderer. He walks in with the moon and rolls out with the wind. He uses no name; the smells of rank sweat, dirt, and smoke mark him as much as anything. He's always near, but never close. Heedless of human ideals and bounds, he stands unyielding for honor on the ground. He's practical to a fault when he's not romantic to even greater fault. He says little, but when he does finally speak, we listen up. The Wanderer is our lawman of final resort. By hook or by crook, he sees a job done, just don't ask how. Frankly, we're a little afraid of the Wanderer. Diabolus, the devil's advocate. Sometimes we are tempted to embrace the evil world that we despise. Diabolus is there to encourage us in this folly. Fortunately a rare visitor here.

Diabolus, the devil's advocate. Sometimes we are tempted to embrace the evil world that we despise. Diabolus is there to encourage us in this folly. Fortunately a rare visitor here.